Big networks, small kitchens, & heavy phones

This week we look deeply at the idea of “scale”, or the size and reach of an idea or service. Being big has its benefits and drawbacks, and while being small can feel precarious, it also means the ability to be nimble and to solve fewer problems at once. Read on to learn how to make your own social network, to see how regulators can fight scale effectively, and how some restaurants are building new businesses out of structures no bigger than a parking spot.

—Alexis & Matt

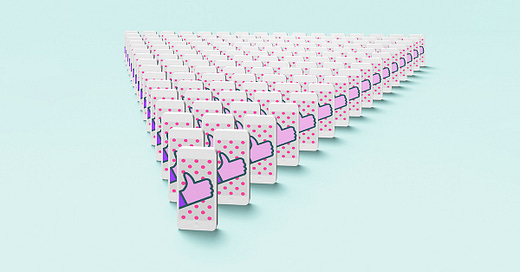

1: Scale, networks, & disinformation

In the wake of the January 6th riots at the Capitol, we’ve seen another wave of thinkpieces grappling with the role of social networks in spreading disinformation that can not only misinform, but actively lead to radicalization and violence. This HBR piece zooms out to give a high-level summary of the problem. Social platforms are built with a focus on growth and scale; scale is achieved by engaging as many people as possible for as long possible; and provocative, sensational content drives engagement very effectively. However, the article is light on solutions: it gives a nod to the ideas of reducing scale, increasing moderation, and tech companies proposing regulatory policies.

Content moderation is indeed critical, and it’s one thing we’ve seen work effectively to curtail disinformation. But we really need to discuss why these platforms pursue scale and growth in a way that is damaging. The underlying cause here is primarily advertising and the foundational business model of most of these platforms. Ad-supported models mean that the only incentive is scale, because the customer is the advertiser, not the user. Advertising has also driven huge swaths of fake scale — fake accounts, fake followers, fake clicks — with no incentive on the part of either advertisers or platforms to address fraud. If social platforms were supported by the dollars of their users, such as in a subscription model, then the incentive is to create a product that users enjoy and value enough to pay for. But in an ad-driven model, the goal is always to optimize for more clicks — even if they are outrage clicks, even if they are fake clicks, and even if they are actively contributing to the erosion of truth and democracy.

→ How Social Media’s Obsession with Scale Supercharged Disinformation | Harvard Business Review

2: Thinking smaller scale

Darius Kazemi and others have been thinking about the scale / business model problem for a while and have been experimenting with small, independent social networks, often run on open-source software like Mastodon. He points to many problems with larger platforms like Facebook and Twitter as motivation, including this (which echoes the points above):

“Because of their need to have as many users as possible, big social network sites have to try to be everything to everyone. In practice this means they need to limit the number of people they alienate, which means they have to be very careful about what kinds of actions and speech they ban on their network. Every person they ban from their network is another set of eyeballs that could otherwise be looking at advertisements and making them money.”

Darius describe the advantages of running your own independent social network: You control the computers that run the software, you can have hyper-specific social norms, you can modify the software, and more. In the guide below, he lays out a set of suggestions for how to get started and how to help your community flourish. It’s a pretty inspiring read — we’ve been running a small community hosted on Slack for a while now, and this made us curious about other kinds of models for that group.

→ Run your own social | Darius Kazemi

3: From purpose-built to flexible physical spaces

If you’ve been reading our newsletter for a while, you may know that we’re obsessed with ghost kitchens, so we were intrigued to read about REEF, which is taking the ghost kitchen concept to the next level. What REEF does is it leases parking spaces in garages and installs a “pod” that contains all the equipment one would need in a commercial kitchen. Each pod can support up to six different restaurants or food brands, and 2-4 people can work in a pod per shift. The pitch from REEF is that they give restaurants the ability to scale their brand into new markets without the kind of startup and overhead costs that they would otherwise bear. So, David Chang is using REEF to extend his Fuku chain into Miami, even though he has no brick-and-mortar Fuku restaurants there.

So, why are we obsessed with ghost kitchens? It’s not because of the food (although we really want some fried chicken now). Ghost kitchens are just a harbinger of how our relationship with physical spaces is changing in a way that may radically reshape what our cities look like. For most of human history, physical spaces have been purpose built and designed. A house is a house, a restaurant is a restaurant, a store is a store. But what if physical space is becoming more abstracted and flexible? Pop-up shops and ghost kitchens may be the first steps toward buildings and structures that can adapt and change as needed.

On the one hand, as shopping and dining is increasingly experienced through home delivery, there is less need for an in-store experience. This leads to things like ghost kitchens or last-mile warehouses that decouple the product from the space. On the other, you could imagine in-store experiences that are more fluid and ephemeral than they have been in the past. A company develops analytics that anticipate shopping trends, they rent something like a REEF pod (which may be autonomous and mobile), and can spin up a new brand or store at low cost and at a moment’s notice. The same trends we’re seeing with Instagram brands that get started with only access to a supply chain and some digital advertising may start to shape the spaces around us as well.

→ Your delivery order may be cooked in a parking garage | Heated

4: How to make Google and Facebook care about privacy

Companies like Google, Facebook and others who are found to have violated their users’ privacy rights are often punished by monetary fines. Historically these fines were relatively small, but even with Facebook’s record-breaking $5 billion fine from the FTC in 2019, these amounts are typically small fractions of annual revenues or even cash on hand.

Recently a photo app called Ever was found to have been using the pictures its users took to enhance its facial recognition algorithms, which it then sold to law enforcement agencies and other customers, in violation of FTC rules. Rather than impose a fine, the FTC instead ordered Ever to delete the algorithms they had developed using the misused photos, as well as the photos themselves. This column by Cathy O’Neil at Bloomberg argues that this is how the FTC should handle privacy violations in ways that will actually have a deterrent effect: force Facebook, Google, and other violators to delete the work product they developed from breaking the rules. More than any single fine, this requirement would put significant portions of their businesses at risk, and would likely lead to better privacy protections for their users.

→ How to make Google and Facebook care about privacy | Bloomberg

5: The constraints & possibilities of a decentralized internet

There’s a lot to unpack in this list of essays and stories about a new decentralization movement on the internet. Helpfully it begins with some of the seminal work that defined internet protocols, specifically the idea that a network of interconnected nodes could be constructed to withstand any attack, even a nuclear strike that could take out a city.

We encourage you to take a look, but with some caveats. First, “decentralization” of the network was always the goal; Internet Protocols were defined such that a message could always get from sender to recipient. We’re a long way from that now, but not because of Amazon Web Services’ market dominance. Rather, the major interconnection points (the “Internet backbone”) are managed by just six companies around the world. The locations of their data centers are carefully guarded, since a successful strike against one could severely cripple the network.

Second, much of the “decentralization” these new essays discuss involves decentralization of content storage and distribution, which is a completely different issue. Here, one could argue that decentralization would make it impossible to censor revolutionary thought, impossible for a government to unilaterally shut down a service for breaking a rule, and impossible for an idea to be pulled down from the Internet. When framed as a fight for freedom these tenets can sound lofty. Consider, however, those same tenets, but in the case of child exploitation, hate speech, or incitement to violence. Today, AWS can decide to “deplatform” a company like Parler, but in a blockchain-moderated web, those posts and videos would live everywhere forever, no matter what harm they caused.

→ The decentralized internet is coming | Protocol

6: “I hope this thing works”

This interview is fantastic, and you should read and/or listen to the whole thing. Martin Cooper, the Motorola employee who helped invent the cell phone, gives a wide-ranging interview after his memoir, “Cutting the Cord”, was published. We’ll leave the best for you to discover on your own, but we were struck by a few specific observations:

Having a rival can force one to take bigger bets, and ultimately, achieve more than they could have on their own. Motorola’s race against AT&T, still a regulated monopoly at the time, was what pushed Motorola execs to fund a “bet the company” project.

When inventing something new, focus on the core problem first. Cooper’s team met to review prototypes for the first cell phone, and many of the ideas predicted forms that would follow later: flip phones and slider phones were among the early prototypes. They chose the simple, brick-shaped “shoe phone” because it had fewer parts to break and would be easier to execute quickly.

Inventions often take on lives of their own. Mobile data and telephony have completely changed society and enterprise since the first brick phone was developed. Did Cooper ever consider what his new invention would bring to the world? No: “I really think that we were visionaries. We stuck our necks out on that thing. But when people asked me what I was thinking of when we made the first public call, it was, ‘I hope this thing works.’”

→ The future of the cell phone, according to the man who invented it | Protocol

One AR creation app

“Rememory is an application that records spatio-temporal data (time-series 3D capture data) and allows you to edit and share it as data that can be played back in AR. 3D data can be edited to create unprecedented visual expressions and can be used as new media for more immersive experiences than other existing formats.”